Causal faithfulness and the hot hand “fallacy”

Psychologists Gilovich, Vallone and Tversky famously argued that the concept of a “hot hand”—the phenomenon where a basketball player seems to enter a kind of flow state and make consecutive shots at a higher probability—is merely a cognitive illusion sparked by the human tendency to see patterns where they don’t exist. This claim did not pass muster among players, coaches or pretty much anyone else, but it sparked a debate that focused largely on methodological aspects of the original work.

I was reminded of all this as I was watching the Thanksgiving NFL game between Vikings and Patriots (yes, that’s very Americanised of me). In the game, the Vikings wide receiver Justin Jefferson seemed to be head and shoulders above the rest (literally), and it seemed to me like the Patriots defenders were constantly trying to mark him as the result. This kind of defending makes sense if a team has a particularly strong player, and it would also make a lot of sense if a player had a hot hand.

In fact, some years ago, researchers raised the objection against Gilovich, Vallone and Tversky, that they failed to consider the behaviour of the opposing team (among other things) when estimating whether the hot hand truly exists. Using a dataset that included the position of the defender and other variables related to the difficulty of a shot, they found evidence that the hot hand exists after all. The idea is that, when the opposing team realises that a particular player has a hot hand, they start marking that player more closely. But because the player is in a flow state, she or he will continue to make shots even under the increased pressure. Players, coaches and fans correctly interpret the player as having a hot hand.

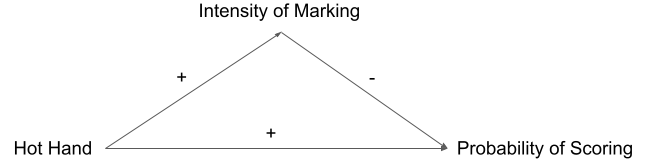

What does this all have to do with causal inference? Consider the following graph which shows the causal structure being proposed (ignoring other variables than the defender’s position):

In this graph, the hot hand has a positive effect on both the probability of making a shot, but it also has a positive effect on close person-to-person marking. More close marking again has a negative effect on the probability of making a shot. These two pathways might cancel each other out, resulting in no apparent relationship between the hot hand and the probability of making a shot.

This is one of those rare cases that are interesting both philosophically and practically. It is philosophically interesting because it poses a problem for probabilistic theories of causation, which try to define causal relationships as ones in which the occurrence of an event raises/lowers the probability of another event. It is practically interesting, because it poses a problem for discovery algorithms that try to learn causal structures from observed data. Such algorithms have a hard time with relationships in which variables are causally dependent but probabilistically independent. In fact, causal discovery algorithms generally assume that such “coincidences” don’t exist. If they do exist, the data is said to lack “Faithfulness” to the structure that generates it. Consider what Richard Scheines, one of the pioneers of causal discovery algorithms, has to say about violations of faithfulness:

Although at first this seems like a hefty assumption, it really isn’t. Assuming that a population is Faithful is to assume that whatever independencies occur in it arise not from incredible coincidence but rather from structure. Some form of this assumption is used in every science. When a theory cannot explain an empirical regularity save by invoking a special parameterization, then scientists are uneasy with the theory and look for an alternative that can explain the same regularity with structure and not luck. In the causal modeling case, the regularities are (conditional) independence relations, and the Faithfulness assumption is just one very clear codification of a preference for models that explain these regularities by invoking structure and not by invoking luck. By no means is it a guarantee; nature might indeed be capricious. But the existence of cases in which a procedure that assumes Faithfulness fails seems an awfully weak argument against the possibility of causal inference. Nevertheless, critics continue to create unfaithful cases and display them.

Scheines seems to dismiss violations of faithfulness as incredible coincidences that we pretty much don’t need to worry about. But the hot hand example doesn’t seem like some far-fetched extreme case. Rather, it seems like something that happens regularly in competitive settings and other designed or evolved dynamic systems. If this is true, then the lack of faithfulness will be a major problem for many otherwise promising application of causal discovery methods.